The Story of Columbus

THE STORY OF COLUMBUS

Early trade with the Orient. In the middle

of the fifteenth century, when Christopher Columbus was a boy living in

the large and busy seaport of Genoa, Italy, the richest countries in

Europe were those bordering on the Mediterranean and Adriatic seas

Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal. These countries had grown rich

largely through their commerce with the East. For centuries, merchants

in the prosperous cities of southern Europe had carried on a large trade

with Persia, India, China, Japan, and other countries of Asia that vast

region being then variously called the Indies, the Orient, or the East.

(This commerce was one of the important results of

the Crusades. The Crusades were expeditions of thousands of Christian

men from western Europe, who in the eleventh, twelfth, and thirteenth

centuries made several partly successful attempts to capture the Holy

Land from the Turks and Saracens. These expeditions cost enormously in

life and treasure; but they were the means of bringing into Europe a

knowledge of new peoples, countries, ideas, and customs, and were

therefore of far-reaching benefit.)

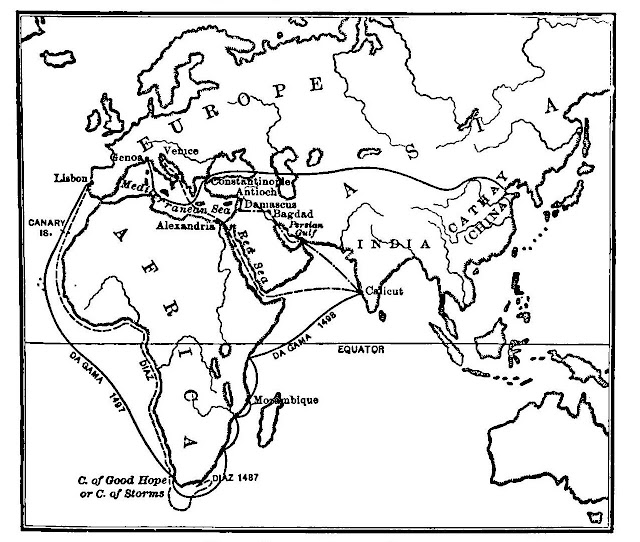

Fleets of ships, laden with lumber, metals, and

heavy manufactured goods, destined for the Indies, were continually

sailing from European ports. Some of them went to Alexandria, on the

north coast of Africa, whence the goods were carried over the Isthmus of

Suez to the Red Sea, and thence by vessels direct to Asia. Other ships

went by way of Constantinople to ports on the Black Sea. Here, cargoes

were loaded on the backs of camels and horses. Long and picturesque

caravans of these animals, guided by drivers in the strange costumes of

the Orient, slowly journeyed across the Asiatic mountains, deserts, and

plains, to the far-off merchants of the Indies. The same caravans and

ships brought back to Europe the products of Asia - ivory, precious-

stones, gold and silver jewelry, silks, perfumes, and spices. Thus

Europeans obtained many comforts and luxuries, which they could not

otherwise have had.

Trade Routes Before Columbus

This commerce with the Indies employed thousands of

men on land and sea; it greatly enriched the cities engaged in it, and

European merchants regarded it as the most important business in the

world.

The trade with the Orient is interrupted.

But in 1453, when Columbus was perhaps six or seven years old, there

occurred an event of the greatest importance. The warlike Turks, who

were Muslims, and hostile to Christians, captured much of the eastern

country crossed by the traders, and after this robbed the European

caravans or forbade them the right to pass through their lands. The

people of southern Europe were thoroughly aroused by this great calamity

and declared that a new way, wholly by sea, must be found by which to

reach the Indies.

Barriers to ocean navigation. However, the

finding of a new water route to Asia proved in those days to be a very

difficult undertaking. There were several reasons for this:-

(a) Ideas about the size and shape of the earth.

Although the people of southern Europe were then the most intelligent

and best educated in the world, they had no idea how large the earth

really is. Besides their own continent, they knew of but two others,

Asia and Africa; and their knowledge of these was very slight. As for

the Atlantic Ocean, it was as yet a great uncharted sea. Moreover, few

people had come to realize that the earth is a great sphere whirling in

space; instead, most of them thought that it was exactly what any part

of it seems to be a great, immovable plain. What was beyond the edges of

this plain, probably they did not dare even to imagine. To be sure,

hundreds of years before this time, learned scientists like Aristotle

and Ptolemy had declared their belief that the earth was round; but in

the boyhood of Columbus, only a few of the more thoughtful and

intelligent men had come to accept what every child is now taught as one

of his first lessons in geography.

(b) Fear of the ocean. With these mistaken

ideas about the world, it is not strange that most of the sailors on the

Mediterranean had extravagant fears and superstitions about the

Atlantic. To them it was the " Sea of Darkness." They firmly believed

that it could not be navigated at a great distance from shore, because

of violent storms, mysterious winds and currents, whirlpools that would

swallow ships, monster sea-serpents, and other horrible things that

would allow neither men nor vessels to return in safety.

(c) Smallness of ships. There was still

another serious obstacle to the navigation of the Atlantic. The sailing

vessels of Columbus’s day were tiny affairs compared with the great

ships in which we now cross the great seas, and they had very few of the

guides and helps to navigation with which we are familiar. The marvel

is that men ventured out in such vessels at all, even upon the

Mediterranean. As for navigating the great and boisterous Atlantic, few

sailors in our time would dare cross the ocean in a ship like the best

of those of the fifteenth century.

Portuguese discoveries. Nevertheless, while

the majority of sailors continued to be afraid of the " Sea of

Darkness," the bolder spirits among them sometimes ventured to sail upon

it, and gradually became more fearless. The most enterprising of all

were the Portuguese, who began quite early to make long journeys

southward along the African coast, and thus discovered the Azores, the

Madeira, the Canary, and the Cape Verd Islands.

After the closing of the overland routes to Asia by

the Muslim Turks, Portugal was foremost among those countries that

sought to find the coveted sea route to the Orient. Finally, in 1487,

five years before the great voyage of Columbus into the West,

Bartholomeu Dias, of that country, discovered the Cape of Good Hope, the

southernmost point of Africa (The Portuguese did not reach India,

however, until 1498); and it is interesting to know that a brother of Columbus was a member of that famous expedition.

Increasing interest in exploration. These

daring achievements of the Portuguese were gradually, but surely,

changing public opinion about the dangers of the unknown Atlantic; and,

together with the pressing need for new routes to Asia, they helped to

arouse in the more enterprising class of Europeans a keener interest

than ever before in exploration. But there were also other reasons why

such men were now seeking information about strange parts of the world:

(a) Four great inventions. Four great

inventions were now coming into general use in Europe the printing

press, the mariner s compass, the astrolabe, and gunpowder. Through

the printing of books of travel, people could learn about habitable

lands heretofore unknown to them. With the compass, mariners could for

the first time safely venture far into the sea, out of sight of land;

and with the astrolabe, an instrument for ascertaining position through

reference to the stars, they could determine latitude and longitude in

mid-ocean; while gunpowder made it easy -to conquer peoples who did not

have fire-arms.

(It is supposed that the Chinese invented movable

types as early as the tenth century A.D.; and gunpowder was made by both

Hindus and Chinese long before it became known to Europeans in the

thirteenth century. The compass may have been used by the ancients long

before the Christian era. Although known as early as the second century

B.C., the astrolabe was perfected by Portuguese

scientists while Columbus was still a boy; better instruments, however, have since taken its place.)

scientists while Columbus was still a boy; better instruments, however, have since taken its place.)

(b) Belief in a sea east of Asia. Among the

more keen-minded of the navigators of the day, a belief was growing that

the Indies might be reached by sailing directly west ward. Marco Polo, a

Venetian traveler of the thirteenth century, had written a book about

his travels in the Far East, in which he had told of a sea lying east of

Asia; and although few people fully accepted his story, it had caused

some of the best geographers and navigators of Columbus’ day to believe

in the existence of such a sea.

(Marco Polo was the most famous traveler in his

day. He traversed a large part of Asia and spent many years in China.

His remarkable book is well worth reading, for much of what he wrote is a

true and vivid account of Asiatic men and things as they were in the

thirteenth century. Most Europeans of those times, however, thought that

his tales were merely inventions.)

Columbus in Portugal. Among these shrewd and thoughtful men was Christopher Columbus. It

is not certain just when Columbus was born, but probably in 1446 or

1447. Little is known about his family or his early boyhood, except that

his father was a weaver. When some fourteen years old, he became a

sailor, and for several years had many wild and daring adventures on the

Mediterranean, for in those days the fleets of rival cities were often

at war with each other. In this rough school of adventure, young

Columbus quickly developed into a fearless navigator.

Christopher Columbus

Columbus decides to make a voyage into the West. Columbus

became satisfied that the earth is round, and thought that the western

ocean must surely offer a short, direct highway to the Indies. While

still a young man, Columbus was attracted by Portugal’s fame in matters

connected with exploration, and went to Lisbon, where he earned his

living as a map-maker. Here he met and talked with the most skillful

geographers and navigators of the age, whose beliefs regarding the shape

and size of the earth were much like his own. From Portugal, too, he

sailed on several long voyages over the Atlantic southward to the

equator, and again far into the northern sea to Iceland.

(Norwegians first settled Iceland about 870. Some

of the Icelandic Norwegians settled Greenland in 986. About the year

1000, some of their descendants, under Leif Ericson, planted a colony on

the North American continent, probably in Nova Scotia, and called it

Vinland (or wine-land), because of the wild grapes found there. This

settlement lasted for a long time, but was always weak and at last was

abandoned.)

The Atlantic, therefore, had no terrors for

Columbus, and a daring scheme for making a voyage into the West in

search of the Indies took final shape in his mind. In addition to

finding a new trade rout to Asia, Columbus also wished to be the means

of bringing Christianity to the heathen peoples of that far-off land.

He seeks aid. Columbus, however, while a

good navigator was poor in purse. He had no money with which to buy

ships and pay and feed sailors, and it was necessary for him to apply to

some government for aid in fitting out his expedition. Accordingly, he

first presented his plan to the King of Portugal; but the King said he

was a dreamer and turned him away.

(The crafty King, nevertheless, secretly sent one

of his own navigators out into the ocean, to see what was to be found

there. But the man returned after a few days of westward sailing, to

report that he had met nothing but fierce storms which threatened to

destroy his ship.)

Thereupon Columbus asked the aid of Portugal’s rival, Spain, whose rulers were King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella.

(Ferdinand was King of Aragon, a part of Spain;

Isabella was Queen of Castile, another part. By marrying, they united

their two kingdoms.)

Just then, however, they were having a long and

fierce war with the Moors, and had little time or money to spare for

explorations. They gave Columbus a small salary and kept him waiting

seven long weary years without deciding whether or not they would help

him in his proposed voyage.

(A council of learned men had been called together

by the King and Queen, to consider the plans of Columbus. In spite of

all he could say, they would not believe that the world is round. They

said that if a ship were to sail beyond the edge, it surely would tumble

off; or, if the earth were actually round, as he stated, the vessel

would slip downhill, where the earth began to curve. "If this

were true," they asked, " how could the vessels get back again to

Spain? " It was unreasonable, they said, "to suppose that men could live

on the other side of the earth; for they would have to walk with their

heads downward, and rain and snow must fall upward." They reported to

Ferdinand and Isabella therefore, that Columbus’s ideas were "vain and

impracticable," and rested on grounds too weak to merit the support of

the Government.)

Meanwhile, the poor navigator, who thought and

dreamed of little else, tried hard to get the English and French kings

interested in his scheme; but they, too, were busy with wars, and told

Columbus that they had no time to talk with him about mysterious

countries on the other side or about the converting of heathen peoples.

Such treatment was galling to an ambitious man like Columbus, firmly

believing, as he did, that he was bound to succeed if only he were given

a chance, and convinced, through his deep religious fervor, that the

Creator had selected him to perform a great work.

The expedition starts. At last, however,

Columbus’s perseverance was rewarded. The wise and generous Queen

Isabella consented to help him, with her husband s cooperation, to make

the trial voyage. Columbus was now a man of about forty-five, but had

grown gray and old from his many years of trouble and anxiety. He was

placed in command of three small sailing ships the Santa Maria, the

Pinta, and the Nina which had been fitted out for the voyage at the port

of Palos. The crews consisted of about a hundred men.

The Queen gave over two thirds of this funding, and

the King the remainder. The vessels were provided free by the town of

Palos, which also supplied cannon and ammunition; and several private

persons helped to meet other expenses. The Santa Maria, the largest of

the three ships, called "caravels," was of about 200 tons, only 65 feet

long and 20 feet broad, about the size of one of the sailing boats that

in our day fish off the coasts. The largest steamers crossing the

Atlantic in our time are of 66,000 tons, and nearly 900 feet long.

Columbus was created admiral and took for his

flagship the Santa Maria, the largest vessel ; and the monarchs declared

him viceroy and governor of "all the islands and territories which he

may discover or acquire." His reward was to be a tenth part of the

profits of the voyage.

Half an hour before sunrise, on Friday, August 3, 1492, the little fleet started upon the world s most famous voyage. To

the people in Palos, who watched the vessels silently steal out into

the broad ocean, this seemed the maddest and most hazardous adventure of

which they had ever heard.

Was Columbus Jewish? - There has been some speculation that Columbus may have been secretly Jewish. On March 31, 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella proclaimed that all Jews were to be expelled from Spain.

The now famous voyage was not funded by Queen

Isabella alone. Two Conversos (Conversos were Jews who were forced to

renounce Judaism and embrace Catholicism.): Louis de Santangel and

Gabriel Sanchez advanced Columbus an interest free loan of 17,000 ducats

to help pay for the voyage, Rabbi Don Isaac Abrabanel, a Jewish

statesman did the same.

Columbus was originally scheduled to sail on August

2, 1492, a day that happened to coincide with Tisha B'Av, a fast

commemorating the destruction of both the First and Second Temples. Columbus

postponed this original departure date by one day to avoid embarking on

the holiday, which would have been considered by Jews to be an unlucky

day to set sail. Instead they left on August 3rd, 1492, the very day that all Jews were required by the edict to leave Spain.

On the upper left-hand corner of all but one of the

thirteen letters written by Columbus to his son Diego are two

handwritten Hebrew letters BEIT and HEY. This is a traditional abbreviation for the Hebrew b'ezrat Hashem

("with the Lord's help"). For centuries it has been the custom of Torah

Observant Jews to add this blessing to their letters. None of Columbus'

letters to outsiders have these letters. The only letter to Diego in

which he omitted these Hebrew letters was one meant for King Ferdinand.

The voyage. Some time was spent in the

Canary Islands, while one of the ships was being repaired, so that it

was the end of the first week in September before the fleet actually

started toward the west. When land had finally disappeared in the east,

the sailors were overcome by fear, and many burst into tears and

lamentations. The firm and courageous attitude of Columbus, however, did

much to control and quiet his men, although sometimes his patience was

taxed to its utmost by their cowardice. Every time anything strange or

unusual happened, their fear became almost a panic; as when the compass

veered round to the west of the North Star, or when great masses of

seaweed were found in mid-ocean, suggesting shallow water with rocks

beneath. And because the wind had blown steadily from the east for a

long time, they feared that there might never be a breeze from the west

to carry them safely home again.

(The explorers were then in the region of the

"trade- winds, "so called because favorable to navigation and trade. In

many seas, these winds blow for months together in one direction. )

Again they could not account for the great number of land birds that they met. It was fortunate for the whole world that this first voyage across the Atlantic was made in calm and pleasant weather. Yet

the voyage proved so much longer than had been expected that the

discouraged and angry sailors finally plotted to throw their leader

overboard and return home. Even some of the officers joined in the

conspiracy.

Land discovered. But, while they were

plotting, the New World was close at hand. At two o clock on the morning

of Friday, October 12, five weeks after the fleet had left the Canary

Islands, and ten weeks after leaving Spain, the lookout on the masthead

of the Pinta joyfully shouted "Land! Land! " Columbus had won! So far as

was then known, all his theories had been proved true; and his officers

and men, humbled and rejoicing, now looked up to him as a great and

wonderful man. Later in the day the ships cast anchor in the harbor of a

little island in the Bahama group, which Columbus called San Salvador

(Holy Saviour), be cause he had reached it in safety. Most historians

now think it was the one called Watling s Island on the maps of today.

Taking possession of the New World. In full

armor, made more resplendent by gorgeous velvet cloaks, feathered hats,

and flashing swords, the Admiral and his chief officers were rowed

ashore. On landing, Columbus s first act was to kneel upon the sandy

beach and with tears of joy thank "God for his great success. Then, a

cross made of trunks of trees having been set up, and solemn religious

ceremonies concluded, Columbus drew his sword and triumphantly claimed

possession of these lands for his sovereigns, the King and the Queen of

Spain.

The land and the people. The little island

that welcomed these first Europeans to the New World was hilly, and

densely clothed with palms and the rich vegetation of the tropics. The

air was soft and balmy; and in whatever direction the voyagers looked,

the view was entrancing.

The Spaniards gazed in amazement at the inhabitants

who had flocked to the shore to see them. But what must have been the

astonishment of the simple natives, as they beheld these marvelously

dressed, pale-faced men, whose like they had never seen before, who had

come to them in wonderful ships, straight out of the mysterious ocean?

Indeed, so convinced were the timid natives that the

Spaniards were not men but spirits, that they treated them with the greatest kindness and hospitality.

Spaniards were not men but spirits, that they treated them with the greatest kindness and hospitality.

The new land supposed to be India. Columbus

decided that the archipelago he had discovered must be out lying islands

of India; in fact, not till after his death was it known to Europeans

that he had found a new continent. For this reason he called the natives " Indians," an incorrect name that has clung to them ever since.

Searching for wealth. Three months were

spent by the adventurers in sailing among the islands that we now call

the West Indies; but nothing worth trading for was discovered among the

natives, save a few gold ornaments, which showed that gold mines must

exist somewhere in this new land. Cuba and Haiti were visited, and in

Haiti the Admiral built a fort and left forty of his men. (Columbus did not discover that Cuba was an island, although he sailed for a thousand miles along its coast.) When,

the next year, he returned from Spain, he found nothing but the

bleached bones of the unfortunate settlers, who had been killed by the

natives.

Triumphant return. In returning from his

first voyage, Columbus reached Palos, March 15, 1493. As his fleet

entered the harbor, he was greeted by the joyous ringing of church bells

and the welcoming shouts of the people who, a few months before, had

thought him a madman. He had brought with him six Indians, decked out in

paint and finery, and many Indian curiosities, besides rare plants and

stuffed birds. The King and the Queen, then at Barcelona, commanded him

to visit them; and upon the long land journey there, the people thronged

to see and to applaud the great discoverer and his strange companions.

At Barcelona they marched into town in a triumphal procession, escorted

by nobles on horseback, drums and trumpets sounding. The sovereigns

received Columbus as if he were a prince returning victorious from war,

and would not let him kneel at their feet as other men must, but bade

him sit beside them. After hearing the story of his wonderful journey,

they conferred special honors on him and on his family.

Other voyages by Columbus. The following

year, Columbus was sent out again. Even the Spanish nobles were eager to

be of the party; and several large ships were filled with a goodly

company of important people, who thought they had but to pick up gold on

the shores of the new land, and thus become wealthy. Similar

expeditions were conducted by Columbus in 1498 and 1502; but none of

these journeys was more profitable than the first, and from each of them

he and his companions returned home discouraged.

(In 1498, Columbus saw the mainland of South

America, but still thought it to be Asia. Owing to malicious charges

against him that he was tyrannical and cruel toward both the colonists

and the Indians, that he did not send to Spain all the gold that he

found, and that he was seeking to become the in dependent ruler of the

West Indies he was sent back to Spain from this voyage, a prisoner in

chains. But the people were so indignant at this treat

ment of one whom they still regarded as a national

hero, that he was released by the King and Queen. In 1502, he vainly

sought to find a way by water through the Isthmus of Panama, hoping to

find India beyond that. Geographers then believed in the existence of a

route of this sort, which on their maps they called "Southwest Passage"

or "Southern Passage.")

Death of Columbus. The expense of these

several expeditions to the New World had been very great; yet up to this

time the Government of Spain could see no gains from them that might be

measured in money. Columbus there fore lost the favor of his ungrateful

sovereigns, and through the rest of his life was neglected by every

one. The people who once had loudly cheered him as the greatest explorer

ever known in Spain now complained that he had really found nothing in

the West but a wilderness peopled with savages and insects, and

mockingly called him " Admiral of Mosquito Land." He died in 1506, a

poor, broken-hearted, deserted man, not even himself knowing how

important his discoveries had been.

(He died and was buried in Valladolid, but his

remains were moved later to Seville. About 1541, however, they were

conveyed to the island of Santo Domingo, now called Haiti. In after

years, they were supposed to have been again moved, this time to Havana,

Cuba. In December, 1898, what were thought to be his bones at Havana

were once more taken across the ocean to Spain. There are many, however,

who think that the dust of Columbus still rests in Haiti.)

Long after his death the real greatness of his deed

came to be understood. Men then realized that he had overcome obstacles

supposed by others to be insurmountable; that in breaking the barriers

of superstition and fear, he had not only doubled the size of the known

world, but had set before mankind a splendid example of courage and

perseverance in a noble cause.

Click below to watch a silent film of the life of Christopher Columbus:

Comments

Post a Comment